The official data flow from Washington has gone quiet during the government shutdown, leaving economists and investors searching for alternative ways to track the labor market.

Into that void stepped the Dallas Federal Reserve, which published new research on the “breakeven rate” of payroll employment.

The breakeven rate measures how many jobs need to be created each month to keep the unemployment rate stable given population growth.

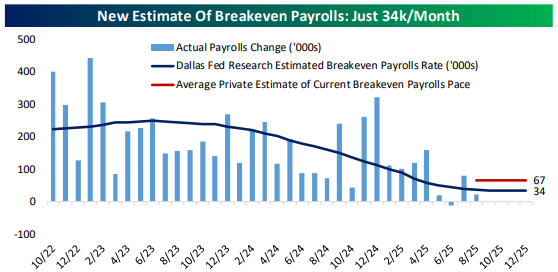

That number has collapsed to just 34,000 jobs per month, according to the Dallas Fed’s latest estimate. A year ago, the figure was closer to 200,000. This reflects a profound structural shift in the U.S. labor force.

Population growth has slowed sharply. Immigration has declined, both legal and illegal, and the domestic labor pool is aging.

The combination means fewer new entrants to the workforce. As a result, the economy can now appear to be slowing even when employment conditions remain tight.

The New Math: Breakeven Falls from 200K to 34K Jobs

The Dallas Fed’s estimate marks one of the steepest declines in the breakeven employment rate in decades.

In 2023, roughly 200,000 new jobs per month were needed to keep employment stable.

By the end of 2025, that threshold had fallen by more than 80 percent to 34,000.

Private sector analysts who run similar models estimate a somewhat higher breakeven range, around 60,000 to 70,000 jobs, but the direction is the same.

The neutral pace of job creation required to sustain the labor market has plunged.

The shift explains why payroll growth has looked weaker over the past year even though job openings remain high and layoffs are limited.

In 2022, when population growth was stronger, job creation was running far above sustainable levels.

Now the demographic inputs have changed, and a much smaller monthly payroll number conveys the same labor intensity.

A payroll print of 100,000 today would be roughly equivalent to 400,000 jobs under last year’s population dynamics. What once looked like stagnation now looks like balance.

What’s Behind the Shift: Immigration and Labor Supply

The new math stems primarily from changes in immigration and labor supply.

After years of elevated inflows, the pace of immigration has slowed meaningfully since 2023.

The reasons are complex: tighter border controls, a shifting political climate, and lingering post-pandemic effects on mobility.

Both legal and unauthorized migration have declined.

At the same time, the domestic population is aging.

The U.S. has fewer workers in their prime earning years and more moving into retirement.

Birth rates have not rebounded, leaving fewer new entrants to replace them.

This dynamic matters for how the economy grows.

When the working-age population expands slowly, the economy’s potential growth rate falls, even if productivity is stable.

The Dallas Fed’s model captures this adjustment. It shows that the “neutral” rate of payroll growth has slipped below 50,000 jobs per month for the first time in modern records.

That helps reconcile the recent combination of slower hiring and still-tight labor markets.

The supply side of the economy has become the constraint. There are fewer workers to hire, not fewer jobs to offer.

Implications: A Labor Market That’s Stronger Than It Looks

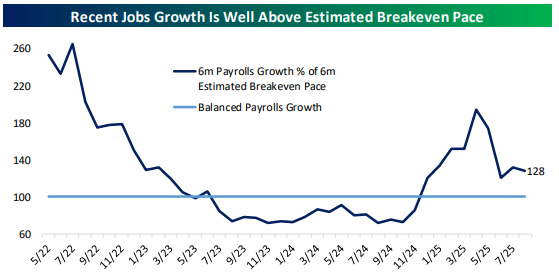

If the Dallas Fed’s estimate is right, recent payroll numbers actually point to a labor market that remains well above equilibrium.

Over the past six months, job creation has exceeded the new breakeven rate by roughly 20 percent, even as the headline unemployment rate edged higher.

This reframes the current debate.

For much of 2024 and early 2025, slowing payroll growth was interpreted as evidence that the economy was cooling.

The new breakeven analysis suggests otherwise. Job creation is still running faster than population growth, which implies continued upward pressure on wages and services inflation.

It also explains the mild drift higher in the unemployment rate. The increase may have less to do with layoffs and more to do with statistical noise in participation and household survey measures.

In essence, the labor market remains tight, but the metrics we have been using no longer fully capture it.

From a policy perspective, this changes how the Federal Reserve and markets interpret incoming data.

A payroll report showing 75,000 jobs gained in a month would have once been taken as a sign of weakness. Under the new demographic regime, it could mean the economy is running exactly on track.

The Big Picture: Policy and Market Repricing

The Dallas Fed’s breakeven estimate highlights a broader transition that economists have been slow to acknowledge.

For most of the past half-century, the U.S. economy was defined by demand-side constraints.

Growth cycles were limited by insufficient spending or investment, not by labor shortages.

When recessions hit, policymakers stimulated demand through rate cuts or fiscal support, confident that supply could adjust.

That framework no longer fits.

The binding constraint today is labor supply.

Immigration restrictions, demographic aging, and shifts in global trade have changed the equation.

The economy is now limited by how many people are available and willing to work rather than by how much consumers or businesses want to spend.

This shift has profound implications for monetary policy.

If job creation remains strong relative to the new breakeven pace, wage growth could remain sticky even as headline inflation falls.

The Federal Reserve may find it harder to declare victory on inflation without allowing some loosening in labor demand.

Conversely, a payroll slowdown might no longer signal economic weakness, making it harder to time rate cuts.

For markets, it means rethinking what constitutes a “soft landing.” Slower job growth may no longer imply recession. It may simply reflect an economy adapting to a smaller labor base.

Equity investors who equate declining payrolls with declining earnings may be reading the wrong signal.

The more relevant measure is whether productivity and wage gains offset demographic drag.

Read our newsletter to find out more about the labor market and US economy.